A Magnificent Catastrophe

Pulitzer Prize winning author Edward Larson compares the first presidential race to the last, and explains why dirty tricks and a 2-party system are the synergy of democracy in "A Magnificent Catastrophe."

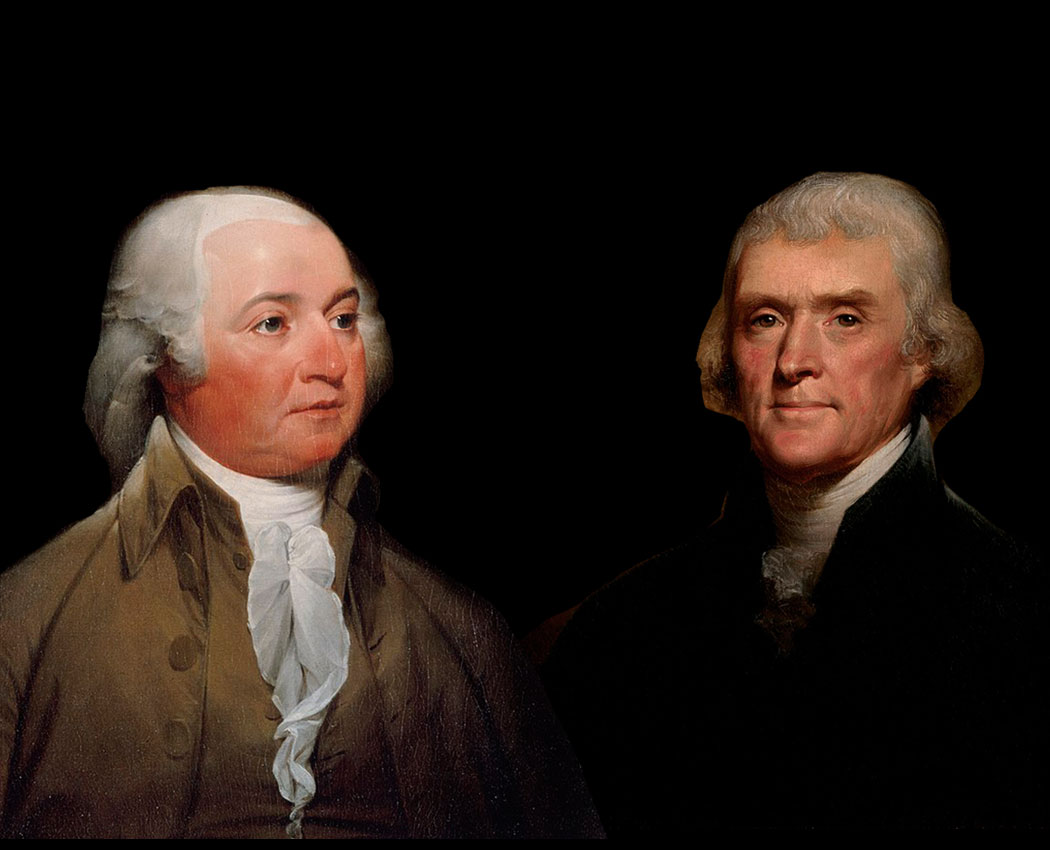

John Adams / Thomas Jefferson

Regardless of political party, bent or persuasion, you may feel the fabric of American politics starting to fray. Nasty political mud slinging. Personal insults. Outrageous media invective. Growing technology. Dire predictions of immigration, accusations of fraud, and constitutional crisis. As much as this seems to describe our present-day presidential contest, it actually describes an election more than 200 years ago. Edward Larson chronicled the First Presidential Campaign in 1800 and holds our Founding Fathers culpable for the dissidence and political practices we experience today. “They could write like angels and scheme like demons,” says Larson, tracing the political careers of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson to America’s First Presidential Campaign, and discovers that the engine of American politics is driven by partisanship.

Donald J. Trump conducted a presidential campaign arguably unlike any other in modern American history. Descending an escalator into the atrium of Trump Tower, he entered the race as a demagogue; praising his golf courses, promising to build a “great wall” on the Mexican boarder, and requiring all American Muslims to register in a national database. He was an unlikely contender, and neither his rivals nor his party anticipated his appeal to the non-college educated, blue-collar conservative right.

It was also a long road for Hillary Clinton — former first lady, senator and secretary of state — whose clear and exceptional qualifications for the presidency were muddied by sound bites and speeches calling her opponent “temperamentally unfit; prone to bizarre rants, personal frauds and outright lies,” and directing that message to a lackluster base of Latinos, African Americans and educated women.

The results amounted to a repudiation of Clinton and Obama combined, and it was a decisive demonstration of power by a largely overlooked coalition who felt that the promise of the United States had slipped their grasp amid decades of globalization and multiculturalism. In Trump — a thrice-married Manhattanite who lives in a marble-wrapped three-story penthouse apartment on Fifth Avenue — they found an improbable champion.

The U.S. Presidential Election of 2016 drew attention and controversy all over the world. Cyber warfare, accusations of rape and groping, even Secretary Clinton’s e-mails were constantly under scrutiny until the end. Indeed, it was a battle of the sexes, multiculturalism, and class struggle. But to understand the 58th United States Presidential Election, we looked back to the very first where fear mongering has its roots and why. I recently spoke with Pulitzer Prize winning author Edward Larson about his book “A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s First Presidential Campaign.”The Election of 1800

George Washington was unanimously elected president by the Electoral College in the first two national elections, and therefore the first and only non-partisan President of the United States. He was an Independent politician who held that “partisanship represents the gravest threat to freedom,” and feared political parties and conflict would undermine America’s republic.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were Washington’s VP and Secretary of State respectively, and naturally fostered factions setting the framework for the First Party System. In fact, America’s First Presidential Campaign saw Adam’s Federalist Party advocating for a strong central government to ensure domestic peace, while Jefferson’s Republican Party feared that a strong central government would devolve the young republic into a monarchy. These were two very different approaches to government, and the terse, ideological rifts that ensued gave rise to the style of bellicose campaigning we see today. Media and Fear

There were only 200 newspapers being published in 1800 and reached all 5.3 million Americans every single day. “Every town had a Republican and a Federalist paper,” says Larson, “and each presented the world from partisan points of view.” Larson points out that newspapers were the only form of communication in 1800, and represented a single, highly concentrated source of information. Today, Social Media and the 24-hour news cycle reach many more with a click, although memes and videos and pics merely make impressions on Americans who now retrieve news only from sources they agree with.

Newsrooms and social media outlets bring big data and sophisticated models to the fundamentally human endeavor of presidential politics, confusing their readership’s insatiable appetites for sensational driven news with erroneous polls, information and opinion. An irony that disconnected the people from truth, disrupted a democratic republic, and ultimately delivered a charismatic reality TV star into the White House.

The misfire on Tuesday night was about a lot more than a failure in polling. It was a failure to capture the boiling anger of a large portion of the American electorate that feels left behind by a selective recovery, betrayed by trade deals that they see as threats to their jobs, and disrespected by Washington, the mainstream media, and Wall Street.

Donald Trump used both traditional and modern media resources to instill fear in the American people. “Hillary Clinton is a criminal,” the republican nominee claimed. “President Barack Obama is the founder of ISIS.” Yet these allegations fall in line with the fear-mongering strategies used by politicians’ centuries ago.

The French Revolution was the topic of the day during the first presidential campaign. It linked the French and American experiments with democracy,” says Larson, “and viewed Bonaparte’s coup as a standing army threatening popular democracy.” Partisan newspapers and pamphlets were filled with editorials that expounded upon and solidified public opinion on both sides of the issue.

Republican newspapers reported the news from France in “Jeffersonian terms” using the press as a political tool to discredit the legitimacy and security of Federalist rule. Conversely, Federalist papers warned against a similarly terrorizing military coup if Jefferson were to become president.

Terrorism, the fear of terrorism, and sensationalizing the fear of terrorism, was a major topic and tool both then and now,” says Larson, “and the election of 1800 set a precedent for negative campaigning by discrediting the opposition through personal attacks and grand accusations.” Negative Campaigns

The first radio news program was broadcast on August 31, 1920, and Franklin D. Roosevelt was the first sitting president to speak over the wires. John F. Kennedy used his physical charm and charisma on television in 1960, and Barack Obama’s masterful use of the Internet in 2008 set the precedent for campaigning in the digital age.

Donald Trump however will forever be remembered for his use of social media. Acknowledging the very social media culture we live in, Trump used the 142 character, insult-slinging, reactionary Internet norm to create a distinctive, unprecedented political brand. By delegitimizing “political correctness” and speaking from a place of calculated vulgarity, Trump compiled a list of platitudes so perverse as to play out in almost every internet culture. He has embraced our reactionary culture to make ludicrous, pervasive, racist, and sexist social commentary not only accessible—but unavoidable. However, negative campaigning is not new and can be traced to newspapers in America’s First Presidential Campaign.

America was a “fundamentally Christian nation even as the nature of its religious establishment was evolving,” says Larson, and this evolution was embraced by many influential Republican figures including Thomas Jefferson. Republicans observed state churches in Europe as “bloated, corrupt hierarchies that invoked irrational superstitions to oppress people and support despots.” Hoping for the freedom from religion as much as the freedom of religion, Federalists felt “secular chaos had replaced Christian order stirring the French Revolution,” says Larson, “and that it could happen in the United States if anticlerical leaders like Jefferson took power.”

Similarly, Republican papers published pieces questioning the character and creed of many Federalist leaders, at times referencing Alexander Hamilton’s extramarital affair and “linking Adams’s public support of civil religion to popular concerns over the authoritarian tendencies of Federalists generally.” These pieces turned private lives into public stories, and effectively set the stage for today’s political climate. Campaigns, Polls & Elections

Donald Trump famously hinted in the third debate that he might not concede, or even challenge the election result. But it was Hillary Clinton who came forth with concessions of support for the democratic process, and the hope for a peaceful transfer of power. Likewise, the presidential election of 1800 was an angry, dirty, crisis-ridden contest that seemed to threaten the nation’s very survival. A bitter partisan battle between Federalist John Adams and Republican Thomas Jefferson, it produced a perplexing tie between Jefferson and his own running mate, Aaron Burr.

The Twelfth Amendment resolved the defect in 1804, but it inspired Vice Presidential candidate Aaron Burr to push political innovation to an extreme. New York City was the most crucial contest of the campaign; capable of deciding the election, and anxieties were at an extreme in the spring of 1800. The challenge of the moment spurred Burr to new heights of political creativity. For example, he compiled a roster with the name of every New York City voter, accompanied by a detailed description of his political leanings, temperament, and financial standing. His plan was to portion the list out to his cadre of young supporters, who would literally electioneer door-to-door; in the process, he was politically organizing the citizenry—not his goal, but the logical outcome.

Similarly, rather than selecting potential electors based on their rank and reputation, he selected the men “most likely to run well,” canvassing voters to test the waters. Perhaps his most striking innovations concerned his advance preparations for the city’s three polling days. As one contemporary described it, Burr “kept open house for nearly two months, and Committees were in session day and night during that whole time at his house. Refreshments were always on the table and mattresses for temporary repose in the rooms. Reporters were hourly received from sub-committees, and in short, no means left unemployed.” In essence, Burr created an early version of a campaign headquarters.

Donald Trump proclaimed that he self-funded his campaign, and in fact spent only half what Clinton did on his way to the Presidency. But in 1800, men simply gave their word and lent their reputation to a cause that ultimately turned into factions, ceremonies, collusions and the First Party System. These honor-pledging rituals were not the party system we understand today, but rather a forerunner to “the continual mischiefs of the spirit of party” which the Father of our Nation warned.Conclusion

In his Farewell Address, George Washington famously wrote “partisanship is the country’s worst enemy." A sentiment entirely lost on a political outsider who consolidated the House of Representatives, United States Senate, and the White House under the Republican Party. “The forgotten men of our country will be forgotten no longer,” said Trump, to a constituency of angry, blue-collar, white middle-aged men who’d been chanting “lock her up” only moments before he took the lectern on election night. President-elect Trump’s “Movement” and “Revolution” sent the peso plummeting and the Dow Jones soaring by Wednesday afternoon, thus reassuring the world that "America will get along with all other nations willing to get along with us.”