New sports cars and mistresses aren’t the only bellwethers of a midlife crisis. There’s often a secret checking account, suspicious credit cards, and overtime that never shows up on the paycheck. There’s the gym, of course, and the plugs and the rugs and the shameless if not convincing shrugs. But while these are the first in a tranche of tale-tell signs observed in men 45 to 65 years of age, scientists are learning that the midlife crisis may coincide with something far more primordial.

In 1965, Elliott Jacques, a renowned Canadian psychotherapist, published an essay on working patterns of creative geniuses in which he coined the phrase — Midlife Crisis. Born in Toronto, Jacques studied medicine at Johns Hopkins University and social relations at Harvard. But it was a last-minute enlistment in the Army during WWII where he used that education to establish the Canadian War Office Psychiatry Division, and to apply his gaze to new recruits, enlisted soldiers, and decorated officers. Moreover, he was able to follow and observe those seasoned armed services veterans throughout the course of their lifetime.

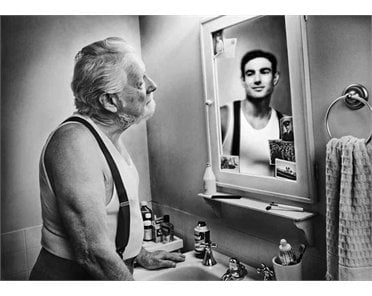

Shifts in their behaviors at midlife were so pervasive they became predictable; feelings of dissatisfaction, nostalgia, and depression all coincided with a sudden inability to enjoy life. Concerns over health and appearance, and compulsive attempts to remain youthful, tried to dial back the inevitable trajectory into the twilight. Even promiscuity during midlife was so common it became a cliché. Considered a psychological theory, rather than a medical diagnosis, Jacques’ Midlife Crisis was manifesting in a plethora of different ways with a single constant. Each and every impulse seemed to connect the middle aged with the young.

The Ego

Considered the Father of Psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud believed that we’re subconsciously driven by the fear of death at middle age. Carl Jung, The father of Modern Analytical Psychology added;

"It's when our projected hopes and promises fail to live up to expectations, and the means of our salvation collapses, that the substantive inner conflict of midlife occurs.”

But it was the Father of Psychosocial Development who went further still. In the seventh of eight stages, Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development squarely coincides and attempts to explain the midlife crisis.

In this stage, men between the ages of 45-65 slowly realize they’re neither young nor old and irrelevant and begin to accept their own mortality. For Erikson, realization and acceptance would trigger a reaction he called "Generativity or Stagnation."

Those who become stagnant weren’t investing in the growth of either themselves or others, while the generative adult stayed engaged. Volunteerism, religious awakenings, and coaching were all venues in which middle aged men sought renewal. Depression and descending into mental illness were the consequences of stagnation. "These are the two trailheads before the elder man," according to Erikson, who held that the preferred psychosocial path is Generativity; a concern for guiding the next generation.

The key achievement of middle age, according to Jacques, was to move beyond youthful idealism to what he called “constructive resignation.” He argued midlife was when we reach maturity by overcoming our denial of death and human destructiveness, though less profound explanations have been offered for midlife dissatisfaction:

It’s when children may be leaving the family home and when adults are generationally sandwiched; required to care for children and aging parents simultaniously. Chronic illnesses often make their first appearance and losses accelerate. Workplace demands may be peaking.

Planet of the Apes

While gender is often proffered to explain the midlife crisis, it may be something far and away more biological. Neither chimpanzees nor orangutans of either sex are known to suffer from existential dread, empty nest syndrome, gender bias or job stress. Yet they both show the same midlife dip in well-being as their human cousins.

Economists and behavioral scientists around the world have studied the pattern of human well-being over the lifespan. They've found in dozens of countries that well-being is high in youth, falls to a nadir in midlife, and rises again in old age. The reasons for this U-shape is speculative. However, a recent study at least hints at an explanation.

Midlife Crisis

Science may explain the midlife pandemonium for those rearing Middle Age.

AP

Alexander Weiss

Alexander Weiss, a psychologist at the University of Edinburgh, and his team recently set out to see if there might be a biological factor involved in the crises. Their study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests the midlife crisis may have its roots in the biology humans share with their closest evolutionary cousins.

"It's common knowledge middle age coincides with a dip in wellbeing," says Weiss, "it's long been observed in many datasets across human cultures. But is it human-specific, driven by gender and social factors, or is there a biological explanation for middle-aged beings reacting psychologically to their age?"

Teams from the US, UK, Japan and Germany asked zookeepers, carers and others who worked with male and female apes of various ages to complete questionnaires on the animals. The forms included questions about each ape's mood; the enjoyment they gained from socializing; and their success at achieving certain goals. The final question asked how carers would feel about being the ape for a week. They scored their answers from one to seven.

More than 500 apes were included in the study in three separate groups. The first two groups were chimpanzees, with the third made up of orangutans from Sumatra or Borneo. The animals came from zoos, sanctuaries and research centers in the US, Australia, Japan, Canada and Singapore.

When the researchers analyzed the questionnaires, they found that wellbeing in the apes fell in middle age and climbed again as the animals moved into old age. In captivity, great apes often live to 50 or more. The nadir in the animals' wellbeing occurred on average at 28.3 and 27.2 years old for the chimpanzees, and 35.4 years old for the orangutans.

"In all three groups we find evidence that wellbeing is lowest in chimpanzees and orangutans at an age that roughly corresponds to midlife in humans," Weiss said. "On average, wellbeing scores are lowest when animals are around 30 years old."

“Maybe evolution needed us to be at our most dissatisfied in midlife,” says co-author Andrew Oswald at the University of Warwick. “Perhaps the unhappiness is a catalyst for change; a self preserving opportunity for renewal?"

Forever Young

They may not take up surfing or be moving into swanky 55+ communities, but chimpanzees and orangutans do at least appear to share the midlife crisis in common with their human counterparts.

When the assumptions by which we live are collapsing, if our worldview presents a surprise, chaos ensues. Chaos is the absence of context, and a critical moment to reset the compass. The need for participation, relevancy and purpose seems critical at all ages. "A tidal wave isn't always a crisis," Jacques observed. "It's a split second opportunity to ride the pipeline."