Sunday Morning / January 6, 2013

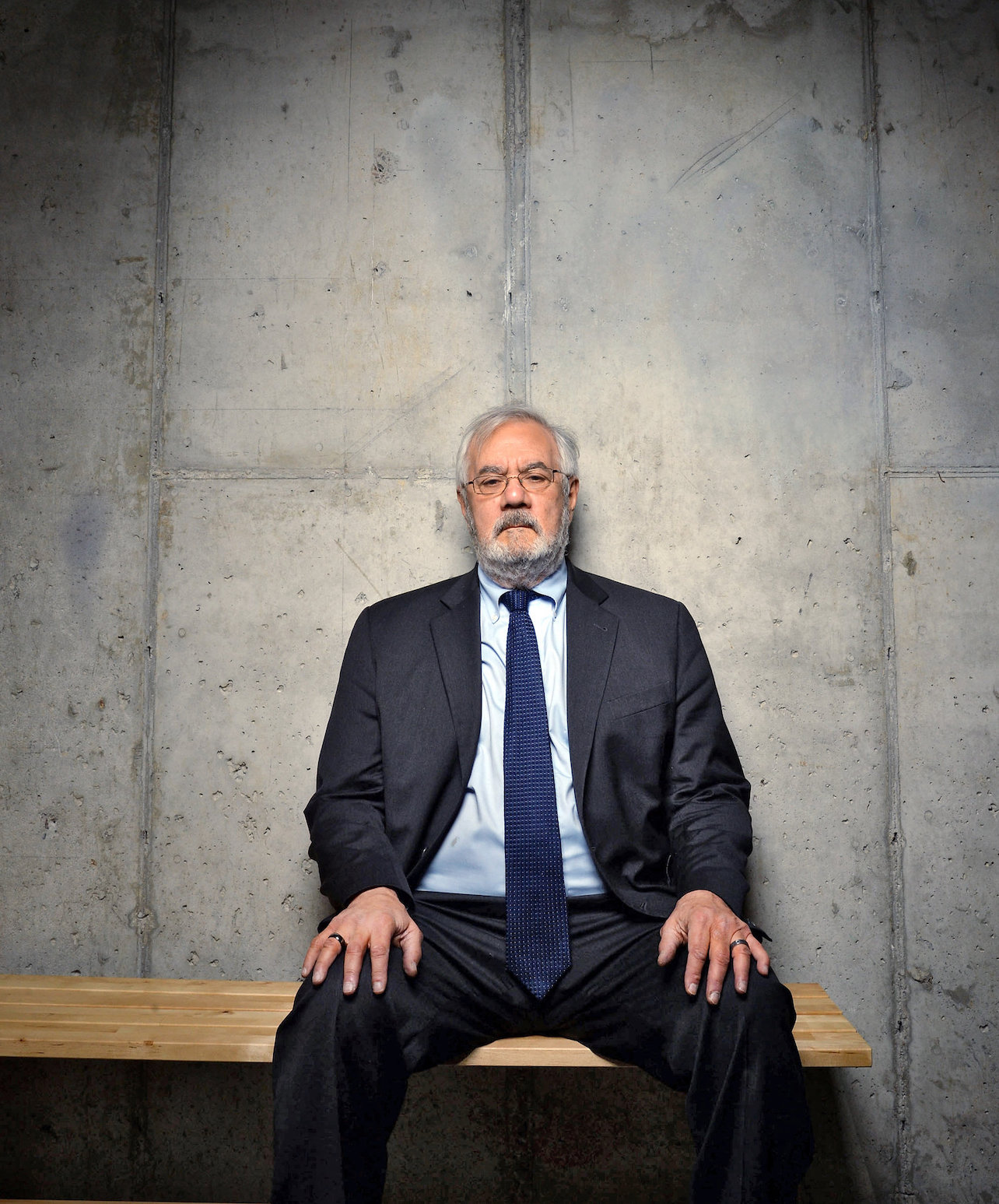

Approaching U.S. Congressman Barney Frank’s office on Capitol Hill is a bit like inching toward the shark tank at Sea World. Visitors beware that sandwiched in a middle unit at 2252 Rayburn Office Building lurks what the New York Times once called a "Salty Old Curmudgeon,” and who after representing the 4th district in Massachusetts for 32 years is finishing up the last of his historic laps through public life.

Rounding the corner to his office on a typically sweltering mid-Atlantic summer morning, I’ll admit pretending not to see the e-mail informing me our meeting was postponed: “The Majority scheduled a series of votes unexpectedly,” the e-mail read, encouraging me to kill time in the cafes along Independence Avenue.

As a former U.S. Press Secretary, I sensed from Members entering his office, and the constituents who’d not been turned away, that our public servant was probably somewhere on the other side of the reception room. “I’m here to see Barney Frank,” I said, easing my briefcase onto the reception desk.

An intrepid woman orbits the tiny reception area, intercepts my arrival, and in an act of administrative housekeeping prepares to eject me from the office. “Didn’t you get our e-mail? The Congressman has been called to the floor and your appointment is postponed until later this afternoon.”

Incensed to at long last be on the receiving end of a buttstroke I’d deployed so many times myself on the Hill I retort, “This meeting has now been rescheduled twice. Is this third and final appointment firm?”

Equal to the task his chief of staff replied, “Yes, it’s firm! The Congressman does need to vote. And I’ll be sure to tell him how rude you were!”

Rude, in fact, had been the very word used to describe the Honorable Barney Frank during his tenure on Capitol Hill by the New York Times, Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal on more occasions than I or my staff could count. As I retreated back into the hallway, Members were indeed gushing through the corridors, onto their private elevators, and into the bowels of Capitol Hill where an underground rail system and secret passageways channel them toward the rotunda. Like a regatta of magnificent ships, each from a unique port of call, they make their way through the halls of congress with our concerns and hopes in their prayer. Long hours and modest compensation do not discourage this group, these men and women, the Members of the United States House of Representatives. And as I stepped from the Rayburn House Office Building, somehow bruised by the encounter, my phone rang with a voicemail asking me to return. “The Congressman can see you now.”

Back through security, up the elevator a second time, down increasingly familiar corridors, and thus I returned to be greeted by a curiously polite Congressman Barney Frank. “Sorry for the kerfuffle,” he says, just a skipper on the ship. “And watch your step.”

Thresholds of marble are made to last, and his quarters offer clues to his legacy and past. Framed pictures, awards and recognitions all puzzle together as somehow more than a Wall of Fame. Indeed, they are the very manifest of his tenure on Capitol Hill.

But as I navigate across the room, I notice on the wall a framed cover of a 1950’s senate report on hiring gays entitled, “The Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government.” Derailing my research I began:

You came to Washington in January 1981 with a liberal agenda and mind to ‘do something’ about gay rights. But you didn’t identify as a member of that group for over 6 years until, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, when homosexuality was on trial throughout the free world, you put the face of a US Congressman on that conversation at perhaps the most visible and volatile moment in the 20th century. Was this a political strategy, or a personal decision that coincided with your circumstance?

It was a personal decision that I hoped would have positive political implications.

I knew I was gay at 13, wanted a political career, and initially thought I could repress my sexuality. But that was crazy. It didn’t work and by the time I got to Washington I thought, okay, I’ll improvise — live as a gay man among other gay people while publicly remaining closeted.

I tried that for years and that didn’t work, either. As I became somewhat better known, the effort to have an authentic life with all of the emotional, physical and psychological needs met in my private life, while remaining ambiguous publicly, became improbable. It was largely a decision that I couldn’t live that way anymore. I was concerned the disclosure would have negative implications for me politically, but I also hoped and believed it would be helpful in the fight against prejudice.

Frank paused, as though looking at himself in the kaleidoscope of his own career, somehow deviating from the stock answers to standard questions he’d rehearsed so many times as the first openly gay U.S. Congressman in 1987.

The AIDS thing, you’re right, was a big deal. Here’s the thing. When I got to Washington, I tried hard to support our rights. But what I found was that people didn’t know who we were, which was a problem, because without transparency we couldn’t counteract the stereotype. They didn’t understand the pain.

The first gay rights vote I was involved in was to repeal the anti-sodomy laws in the District of Columbia. The US House, as it then had under the constitution, had the right to cancel that. I lobbied some good liberals and pled, “Why are you doing this?” They answered, “Look, we know its stupid and we shouldn’t prosecute people, but it’s not a big deal.” In other words what they said was, 'We don’t want to take a risk with an unpopular group when it’s not that important.’ I tried to explain that it was important. But it wasn’t until AIDS came along, with its terrible death tolls, that Members of Congress were forced to acknowledge the epidemic and by consequence the gay community. In fact, the first votes we won, that could be construed as gay rights, were in defeating amendments that denied people with AIDS proper medical treatment. The AIDS epidemic was a big deal, and summarily made the LGBT community undeniably relevant to Congress.

Okay, but when you came to Washington you initially felt it would be a brief stint. Why bother?

I wasn’t sure I’d survive. In 1982 I was expecting to lose my first re-election campaign because of redistricting. Reagan had a program that was unpopular in Massachusetts. My opponent was a republican and something of a moderate-to-liberal who was forced by Reagan to become much more conservative. That gave me a chance to pick up a lot of her support.

And they’re remapping it again?

Every 10 years, given population shifts, districts are reorganized based on a 1964 US Supreme Court ruling that each district must have equal representation.

You were an advisor to GLAD’s Gill v. Office of Personal Management which led to the First US Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston unanimously affirming DOMA’s unconstitutionality. With Interracial Marriage, Abortion, and now same-sex marriage ultimately being decided by the courts, are politicians more a steering committee for civil rights?

First, let me say that the Director of the Civil Rights Project at GLAD Mary Bonauto is our Thurgood Marshall. And I regret the fact that some of these big shots that want to be helpful don’t pay more attention to her. But the political mistake that the LGBT people made, and it’s flipped now, was to assume that if you declare same-sex marriage legal in Hawaii, as happened in 1996, that it will be legal everywhere. That is neither legally true nor politically sustainable.

Marriage Equality, Mary Bonauto at U.S. Supreme Court

However, we’ve since come up with a very good strategy. The suggestion that homosexuality causes trouble in any aspect of society is ludicrous. Demonstrate that, state by state, and expand it. Gill v. Office of Personal Management ensured that people married in Massachusetts are also recognized as legally and lawfully married by the federal government, too. With bi-partisan politics invariably slogging the process, Mary Bonauto is the best bet that this will be heard in due course by the Supreme Court.

Are politicians overshadowed by a judiciary that ultimately legislates from the bench?

No. Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Hate Crimes. The Employment Non-Discrimination Act. The Supreme Court of the United States is the expositor of the US constitution. The court has the duty to review the constitutionality of acts of congress and declare them void if and when they run contrary to the spirit of the constitution. With deference to the equal protection clause, not one of these conversations will ever see the inside of a courtroom. Fairness, however, is not peculiar to the LGBT community. It’s a question that effects everyone in America.

You called the impeachment of Bill Clinton one of the “Great acts of hypocrisy in American history.” Why?

Because the Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, was actively having an affair whilst cheerleading congress to impeach Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky.

Simple as that?

Yep.

Do you think what consenting adults are doing in the privacy of their bedroom is an appropriate conversation for politicians on Capitol Hill?

No. Unless they’re publicly condemning what they privately condone. Hypocrisy should be a conversation.

How is social media changing the political process?

Well, to some extent, it makes it a little bit worse. First, social media is part of a trend where people only hear from and talk to people they agree with. It’s to have the most active people politically living in parallel echo chambers. Second, it can multiply unfortunate cynicism because there are no filters mitigating the misinformation.

So it’s not censored?

Not only is it not censored, but, far more importantly, it’s not filtered. Is it censorship when editor asks their reporter about their source? Anyone can put anything on the Internet without having to demonstrate its accuracy.

Facebook currently has nearly 3 billion users and say they’re targeting all 8 billion people on the planet. How important is social media to the political process?

People used to get their news from one source. Today it’s the Internet, cable, talk radio, streaming and the 24-hour news cycle that enables people to get news only from people they agree with rather than an objective source. The ideological bifurcation of news, regardless of its platform, impacts and confuses people’s political opinions. Complex narratives can't be conveyed in posts, but rather posited as an arc of information to achieve any objectivity of its truth.

You plan to teach in retirement?

Yes. Teach and write about the history of the Gay Rights Movement. The LGBT movement, beginning with Stonewall in ’69, is coterminous with my first election to the Massachusetts legislature in ’72. I’ve been the beneficiary of the progress, and, to some extent, an agent of it.

When did you become interested in Adam Clayton Powell?

I’ve been interested in Adam Clayton Powell contemporaneously with my life in politics. He was a major figure in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. While segregationists in his party controlled seats allocated in the southern states, Powell, together with the NAACP, developed a strategy known as the “Powell Amendments” which required federal funds to be denied to any jurisdiction that maintained segregation. The principle became integrated into the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Moreover, Powell was the third black member of congress. He challenged the informal ban on black representatives using Capitol facilities reserved for white members. He took black constituents to dine with him in the 'Whites Only' House restaurant, and he was the first African American United States Congressman to swim in the 'Whites Only' swimming pool. Although he was the third black Member of the U.S. House of Representatives, he was the first to actively reject his segregated status.

In July, you’ll become the first Member of the United States Congress to be married to a person of the same sex, and you’ve said it’s important for Members of Congress to interact with a gay married man. Will this have a polarizing effect on your colleagues and constituents?

No. It’ll have a de-polarizing effect. People react much more negatively to abstract stereotypes. Reality defeats prejudice.

Respect for Marriage Act 2022 w/ Speaker Nancy Pelosi

Indeed… For on the 4th of July 2012, just 4 weeks after my interview with Frank, the Department of Justice (whose sole commission is to defend federal law) filed two petitions for writs of certiorari from the United States Supreme Court.

In brief, the federal government withdrew from its duty to defend the Defense of Marriage Act, and as lawsuits inched through the legal system and onto the highest court of the land, the DOJ, in fact, the President, asked for ultimate resolution on Article 3 of DOMA.

Denying legally married same-sex couples of the some 1,138 privileges, rights and protections afforded to legally married opposite-sex couples, President Obama asked the Supreme Court to consider what the Gentleman from Massachusetts has been stumping about for 32 years – the question of fairness.

Revolutionaries are known for their rebellion, aggression, and, yes, rudeness. And every fight has a front man. But let the first to waltz with his husband at the White House be remembered a statesman: whose savvy of the political process and hard work combined to pass the torch of revolution to a kinder, gentler nation.