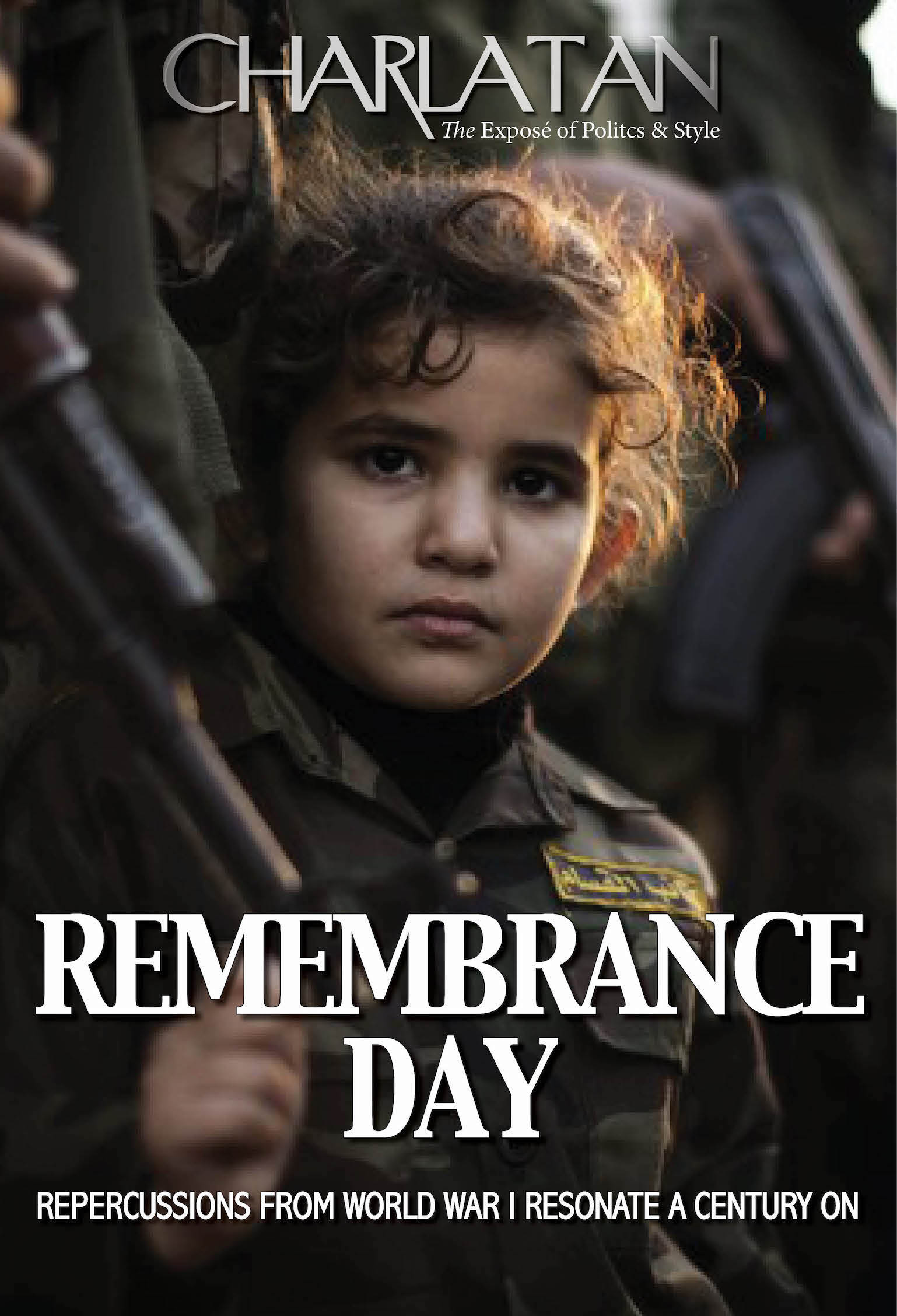

Saturday Morning / November 11, 2023

It’s Remembrance Day, and all thanks to the grand finale o’er World War I on November 11, 1918. Effectively ending all military operations, the Allied and Central Powers of WWI sign the Armistice Agreement in a forest near Compiégne, France; a ritual of remembrance getting under way the following year at Buckingham Palace.

Precisely why 56 sovereign states, about 2.5 billion people, nearly 1/3 of the earth’s population are called upon to remember 17 million military casualties among 10 principal actors 100+ years ago is less clear. Is the pause designed as a warning, deterrent, a victory lap?

The two minutes of silence on the grounds of Buckingham the following year was designated as “a remembrance of the fallen and those left behind” after all, but it was a dinner at Buckingham the night before—a banquet for the President of the French Republic, Raymond Poincaré, where the business of what to remember and why all began.

Through commemorations, rituals and routines their message reaches us a millennium on: Central Powers carved up and partitioned by the Treaty of Versalles; Allied Powers assuming the role of global leadership; and an international holiday thats less about the importance of remembering than about the inevitable consequences of forgetting.

Decolonization

Lots about Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the “shot heard around the world” in 1914, the historically accepted catalyst for World War I. The larger picture reveals the assassination coincided with the world’s major empires all trying to expand their borders.

In the first global conflict fought between two coalitions (Allied Powers/Central Powers) across the Pacific, Middle East, Africa, Europe and Asia, WWI is among the deadliest wars in history, too: 17 million military dead; 23 million civilians wounded or dead; the soldiers of WWI inadvertently carrying the Spanish Flu throughout the world.

However, four years of combat (July 28, 1914 – November 11, 1918) didn’t result in nation building for the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires at all, but rather the dissolution of those empires into new independent states including Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Turkey.

But for the French President Raymond Poincaré, who observed in 1917 an atmosphere of defeatism in France; therefore recalling Georges Clemenceau to the premiership; and the fierce General Ferdinand Foch as the Allies supreme commander, the deceive Battle of Amiens might never have materialized in the annals of history. The German drive was checked by the Hundred Days Offensive and on November 11 an armistice was signed in Foch’s railway car near Compiègne.

Of those who advised national delegations during the negotiations, Mike Heffernan, a professor of historical geography at the University of Nottingham, observes, “they weren’t economists. The war reparations on Germany destabilized Europe, and laid the groundwork for World War II.”

The First World War displaced 12 million people across Europe and the Middle East, all of whom had been stripped of their national identities. Few knew what country they belonged to; where and when their borders would re-emerge; and each and all were drawn into regional conflicts by national movements.

Precisely one year to the U.S. Presidential Election 2024, every conceivable poll shows the presumptive GOP nominee leading the incumbent. A sitting and former president with two very different takes on foreign policy, each are worth considering for Russia > Ukraine > Israel > and the many thousands displaced, missing and dead in Gaza.

America First

Isolationism noun: a policy of national isolation by abstention from alliances and other international political and economic relations. Wikipedia, a free-content online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers expands upon the definition:

AP

A policy or doctrine of trying to isolate one's country from the affairs of other nations by declining to enter into alliances, foreign economic commitments, international agreements, and generally attempting to make one's economy entirely self-reliant; seeking to devote the entire efforts of one's country to its own advancement, both diplomatically and economically, while remaining in a state of peace by avoiding foreign entanglements and responsibilities.

Is the former president an isolationist, as Governor Asa Hutchinson recently observed, or is he channeling the likes of Prime Minister Clemenceau, who, at the age of 76, was an uncompromising republican who promoted nationalism? Known for their energy and vitriol, both succeeded in injecting spirit into their national identity. A risky, perhaps even ambitious effort to court foreign allies while containing global adversaries.

Following the war, when it appeared that the United States was dissociating itself from European affairs, Clemenceau, now retired and 81 years old, began a whistle stop tour through the United States in November 1922.

In an attempt to arouse its citizens from isolationism, he delivered 30 speeches admonishing Americans that if they dare to forget WWI — another would inevitably follow. President Woodrow Wilson accompanied Clemenceau’s peace crusade and pilgrimage to places where French soldiers had fought with Americans in the Revolutionary War.

In 1922, Clemenceau gave a lecture tour in the major cities of the American northeast; defending the policy of France; including war debts and reparations; and condemning American isolationism. In Virginia, he speaks of the Siege of Yorktown:

America is the only nation in history which miraculously has gone directly from barbarism to degeneration without the usual interval of civilization.

Clemenceau is referring to Manifest Destiny, a belief that Americans felt destined to expand across North America, if not the implication of America’s ambition to become a global leader. However, a state in the grip of neocolonialism is not master of its own destiny, as the man who liberated Ghana in ’57 once observed. “It is this factor which makes neocolonialism such a serious threat to world peace."

Those in any way calculating the reoccupation of sovereign territories and states today—such as Ukraine or Gaza, per se—would be wise to Google Khalil al-Hayya, a top member of Hamas leadership:

We hope that the state of war with Israel will become permanent; we hope the Arab world will stand with us; and we hope to unite the Arab world in the Palestinian cause.

To be clear, American Revolutionaries could neither defend their colonies nor prevail against the British Army without the French. Nor could the Allies of World War I and II ever tabulate their destinies outside the Battles of Amiens or Normandy.

Wars are not fought in a vacuum, but rather are a consortium of alliances each vested in the end result. Perhaps why Arab leaders including Egypt > Jordan > Saudi Arabia are now pushing for a cease-fire, and the G7 has called upon Israel for a “humanitarian pause." The original calls for solidarity have turned into caution and restraint as the world begins to accept that behind Hamas’s bloody gambit is a calculation for world war.

At the banquet for the President of the French Republic King George V began:

I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon earth through the years to come than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war?

AP

In the end, the Central Powers of WWI were sanctioned: Germany was fined 132 billion gold marks (US$442 billion today); Austria-Hungary was carved up into smaller nations; and the Ottoman Empire surrendered its territories—including the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem—to the administration of Great Britain.

The McMahon–Hussein Correspondences promised to recognize Arab independence in the region; the Balfour Declaration proffered "a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine;" the Sykes–Picot Agreement between Britain and France proposed to split the difference; and therein lies the kismet of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The historically occupied, mismanaged, and politicized borders of the Jewish, Christian and Arab people became the hollowed apron strings of inevitable wars.

Afterward

After World War I, poppies began flourishing in Europe. Scientists attributed their growth to soils in France and Belgium becoming enriched with lime from the rubble left by the war. From the dirt and mud grew endless fields of red poppies; a symbol of the blood shed during WWI; and a poem written by the Canadian physician Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae.

However, there are two versions of this poem. In Flanders Fields and Other Poems lies the official. But the original, a handwritten copy, inspired during the funeral of his friend and fellow solider Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, wounded and killed in the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, is quite different.

Punch Magazine, the predecessor of Charlatan Magazine, claims to have received permission from the author to change the last word of the first line for publication. Questions over how the first line should end have endured since publication.

Make sense of the week's news. Charlatan reviews the world's show & message.