Ebola

Its was a political cautionary tale for COVID-19. Contributor MATTHEW FLACKS talks with David Quammen about a global pandemic's origins and end game in "Ebola: The Natural and Human History of a Deadly Virus."

Highclere Castle

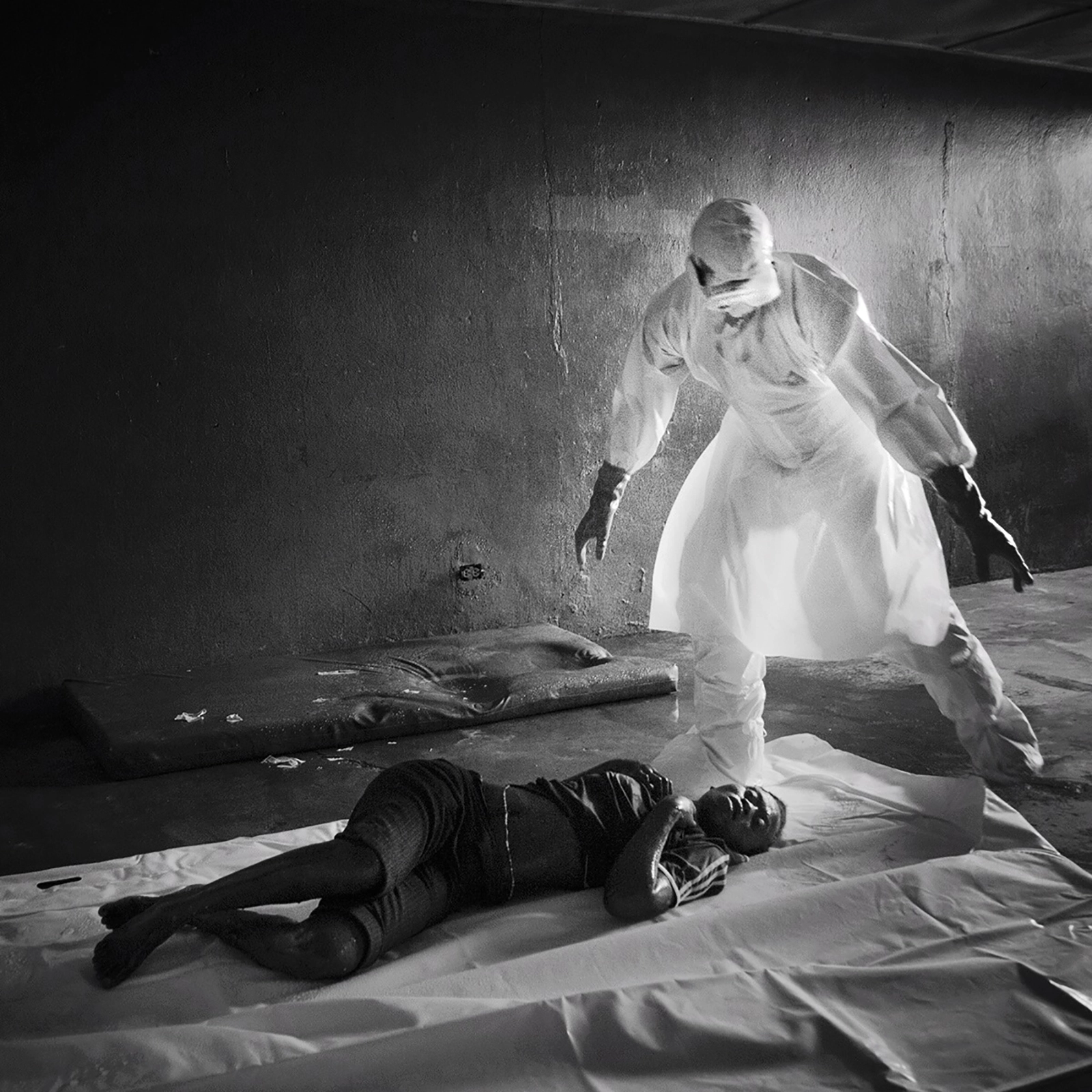

Like a corrupt politician, Ebola has become a villainous celebrity over the past year, prompting delirious narratives and dominating the airwaves. It has been demonised, humanised, and, above all, adulterated. Huge amounts of money have been raised to tackle it, but how much do we really know of this virus, and why has the response to it at times been so lackadaisical, both on the ground and in reportage? Truth tends to be tricky to assimilate so I spoke to David Quammen, an award-winning science and nature writer whose recent book Ebola: The Natural and Human History of a Deadly Virus brings a factual, thoughtful and realistic analysis to what has been a slightly frenzied climate. We know this a deadly virus, but it is also a shamefully political one.

Ebola, like HIV, cholera, and malaria, is a zoonotic disease (spread from animals to humans) and has been in and out of hiding since 1976. When humans come into contact with its reservoir host, be it a bat or a chimpanzee, the virus spreads. The current outbreak, which Quammen explains is very much an epidemic, is concentrated in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. To many in the developed world such countries are simply poor African hinterlands familiar to disease and tragedy and so it is easy to let out a dystopian sigh of sympathy and move on. But when it rolls up on the shores of ‘civilisation’, consciences are pricked. As the Western paranoia subsides, Quammen tells me that this is not a virus attacking on purpose, targeting humans out of spite, as convention may have it, but it is part of the Darwinian maturation.

During this crisis, we have seen and heard some excellent commentary but also a disparate representation of peoples rather than persons. When Ebola touches Madrid, Dallas or London we know the full names, places of birth, even the occupations of those affected. We see images of sprawling hospitals, helicopters and motorcades that fill our imaginative void. Yet take it to Sierra Leone and we find stock images of desperation and poverty that feel somehow customary. We’ve tended toward superficial attempts to seek understanding, butchering reality to feed a collective, patronising compassion. It’s far away, it’s them not us. Newspapers full not of individuals but of the ‘Ebola’ enemy. In the words of Susan Sontag: ‘Footage and photographs nourish the belief in the inevitability of tragedy in the benighted or the backward – that is, poor parts of the world.’

Misconception is rife. Ebola’s perceived expression – its bloodiness, its capability to shut down major organs - has been overegged, according to Quammen. In the eyes of reporting, the possible has overtaken the probable to exaggerate the psychology of the disease. This ‘African’ Phenomenon has come from the forests – not virile death traps ridden with killer snakes and gorillas the size of the Empire State – but beautiful, diverse habitats. However, when man and woman intervene in biodiversity, they can face repercussion. The longer this epidemic goes on, the higher the chance of it mutating randomly, and becoming resistant to human intervention.

International organisations and governments have faced intense criticism. Information has trickled out and has often been either cursory or dramatically alarmist. Quammen has become disillusioned with the World Health Organisation and says ‘their regional directors are filled by political horse-trading rather than public health experience.’ Indeed their curtailed reaction was initially pretty incoherent. As early as January 2014, WHO was briefing against Médecins Sans Frontiers when the aid agency better known as ‘Doctors Without Borders’ asserted that ‘the Ebola outbreak was unprecedented.’ To further boggle the mind, the WHO’s outbreak response unit has had its budget cut by half (£150m) by its 190 member states.

Quammen writes that weakened governance in West African nations from years of coups, juntas, civil wars and loose borders has allowed Ebola’s rapid spread. For example, a chronic lack of investment in health infrastructure has hampered Liberia for decades, and despite its government receiving $60m from the European Union over the last two years, only $4M went to the health sector. In addition, UK aid to Liberia and Sierra Leone was cut by 20% last year and the Ebola epidemic will cost them much, much more. And yet, there is an argument (to which Quammen concurs) that the vast capital being committed to fighting Ebola is diverting resources from the daily challenges of malaria, premature birth, cholera and other lethal ‘African’ dilemmas.

These may seem like acerbic observations and maybe they are. Huge strides have been made in managing the virus and I do not intend to underestimate the challenge that Ebola poses scientifically, medically or socially. Attempting to educate local communities that have strict burial rituals of family members (which aggravates the spread of the disease) can have antagonistic consequences, challenge the very identity of indigenous cultures, and prevent the harbouring of trust between doctors and their patients. The aspect of denial, the claims of sorcery, of dark magic at play, can go to the very heart of a person’s beliefs. It can be a tightrope of diplomacy muddying the medical imperative. It is a perilous situation.

We should accept Ebola as a natural occurrence: one that is unforgiving, restless, unselective, amoral and has no agenda. Equating disease to human character, labeling it with various demonstrative adjectives, misconstrues its random nature and serves little use in finding a cure. Quammen says ‘evolution doesn’t have purposes, it only has results,’ and points out that in order to understand our ecosystems fully, we must understand and accept Darwinian theory, starting primarily at school. It is a slow-moving virus, one that when conquered will not be eradicated, but merely go into hiding.

It is not the epidemic that will cause global catastrophe, though David Quammen contends that one is looming, most likely under the guise of influenza. International consciousness towards Ebola is waning as it becomes chronic rather than acute, despite the fact that huge numbers of people are still dying. The news cycle is moving on, which brings a danger of complacency – continued assistance, expertise and attention are imperative. As global citizens, we must continue to respond, learn lessons, study, not least because an African life should be valued as any other. In theatre, there is a well-rehearsed saying: Forget the drama. Work with the truth.

Archives