An Indigenous Peoples

It is the largest extermination of an indigenous people in history. Contributor MATTHEW FLACKS sits down with historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz to discuss the Removal Act and genocide of "An Indigenous Peoples'.

An Indigenous Peoples'

An Indigenous People’s History of the United States” is a quintessential biography. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has spent seven years of curating the historical context of American national identity and existence. If you have a hardened sense of nationalistic pride and of the great American way, it may be best to look away. Our author challenges emotional and psychological honor so closely associated with the stars and stripes, positing the notion that US history is steeped in genocidal atrocities which may be tantamount to treason to most US patriots.

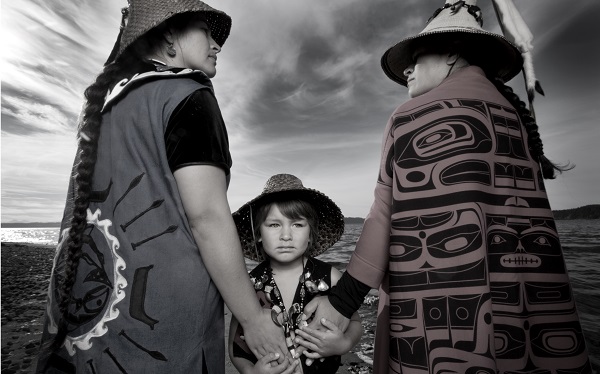

Across the world, there are three hundred and seventy million indigenous peoples, five hundred communities of three million people in the US alone. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, a hugely respected historian and feminist, embraces her revolutionary identity and suggests that her book was essential for establishing social justice movements in the development of a radical political project. She argues that the US was born of ‘predatory militarism’, grounded in settler colonialism and a white supremacy that still exists today. When European settlers transposed their ideas of property to America, they colonised the land of Native Americans, turning it into hard real estate, creating a country that became ‘a crime scene’. The Indian Wars violently opened up indigenous land in the west to relieve the pressures of class conflict and industrialisation in the east. By 1890, almost all US land had been divided and privatised, and yet little is said of such barbarity in the national discourse.

It must be noted that this book is not just an attempt to stir contemporary nationalistic guilt, but rather an attempt to highlight the atrocities inflicted by successive generations and a search for a modicum of redemption for indigenous communities. Of course it is not merely a US-centric phenomenon. Just look to one of the sternest culprits, Great Britain, to see a litany of past horrors inflicted on those inherent communities. Indigenous peoples who live by a collective right to use the common land have been subject, through land grabs, to discrimination, assimilation, displacement and poverty due to the development of communal land as an asset. ‘’The impoverished and marginalised condition of Native Americans must be recognised as a colonial condition intentionally kept in place by the denial of settler-colonialism,’ says Dunbar-Ortiz. ‘This is a life or death situation for Native peoples.’

The historian points out that lauded presidents from Andrew Jackson to Abraham Lincoln ‘washed their hands in indigenous blood’, being the creators of populist imperialism at home and exporting it abroad. Jackson implemented removal policies for many of the five tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw and Seminole) and Lincoln, despite freeing black slaves in the Civil War, also implemented a raw land grab policy.

Even the Dakota Access Pipeline—a 1,172-mile-long underground oil pipeline project from North Dakota to Illinois—is marred by politics. President Donald Trump signed an Executive order to advance the construction of the Dakota Access pipelines on January 24th, 2017, whilst quietly holding between $15,000 and $50,000 in stock in Energy Transfer Partners, the gas and propane conglomerate that instigated this project. While the pipeline tears through sacred indian burial grounds and obstructs clean water sources, Energy Transfer Partners CEO Kelcy Warren was quietly contributing $103,000 to the Trump campaign. According to his transition team this position "has nothing to do with his personal investments and everything to do with promoting policies that benefit all Americans."

So why is a history littered with unedifying, brutal episodes rarely commented on by historians? Dunbar-Ortiz explains that although there has been mobilisation of Native American organisations over the last four decades, there has been little attempt, even by the left, to trace the predatory militarism and capitalism imposed on such communities three hundred years ago. There is a traditional separation of domestic and foreign affairs in the US, and yet the wars against Native nations fell into the foreign affairs category, and hence ignored. Maybe historians would be castigated for the very modern notion of being anti-American. 'You’re either with us or against us is a tired, tedious philosophy.

The author explains that the US ‘culture of conquest’ has survived to the present day and is entirely embedded in the American psyche. Indeed it continues to export such ‘ideals’ as liberation and democratic release, often under the inauspicious banner of ‘the war on terror’ in the present climate of international relations. All talk of a nation of immigrants and the black liberation of the 1960s neglects the settler-colonial core, and the terrible wars waged against the Native communities.

Terminology such a ‘genocidal’ and ‘land grabs’ can rouse worrying concepts of inhumanity and horror. Yet attempting to confront our collective indignity should be a cause for hope. The assumption that the US is not an imperialist state because it was itself born of anti-imperialist liberation is false, says Dunbar-Ortiz. The US was an imperialist annex of the British Empire fully equipped to fashion its own wars against indigenous peoples.

The impoverished and marginalised communities of Native Americans will not be acknowledged until there is a national consciousness of the historical essence of US settler-colonialism, embedded in its constitution. Questioning our propensity on real estate and capitalist ideals goes to the heart of our historical emotional ties to each other and our environment. Dunbar-Ortiz explains that there is presently a life and death situation for Native peoples in America, and until there is recognition that the US (along with other imperialist countries of the past and present who have hardly bathed themselves in glory, Britain included) used land and people as capitalist commodities, nothing will change. This disgrace will continue to haunt the world over unless or until this illuminating fact is accepted and rectified. Otherwise, poverty, displacement, drug dependency and derision will continue, unabated, the world over.

Archives